On the Kind of Love That Rearranges You

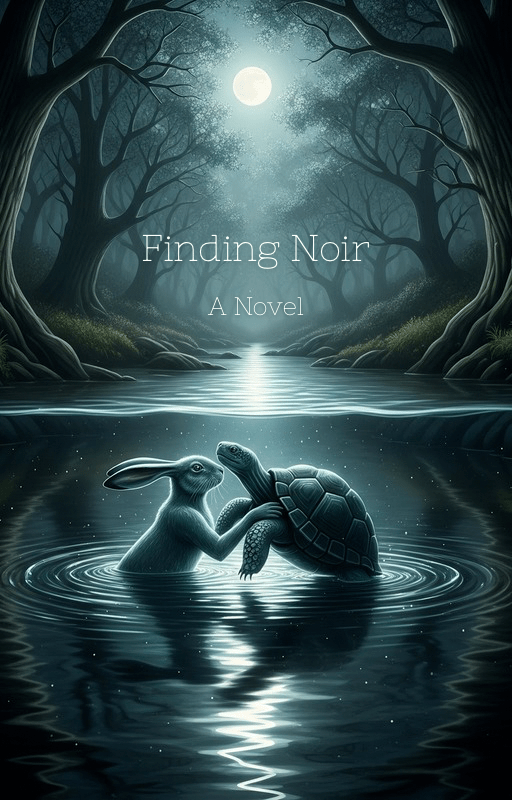

Finding Noir

I didn’t know I was looking for myself when I first mistook it for love.

The moment itself was unremarkable. A conversation that lingered longer than it should have. Not because of anything extraordinary that was said, but because of what surfaced in the pause between sentences. A sense of familiarity without history. Recognition without proof. The kind of encounter that leaves no evidence, only residue.

It wasn’t comforting. It was clarifying.

For a long time, I believed connection was something to be secured—defined by continuity, reciprocation, and effort. I measured its legitimacy by outcomes: longevity, commitment, return. Love, I thought, was something you earned by staying, choosing correctly, wanting carefully enough.

Finding Noir emerged when that framework began to collapse.

I began to notice a different category of connection—one that didn’t orient itself toward resolution at all. These encounters didn’t soothe or stabilize; they destabilized. They rearranged the internal furniture. They made familiar beliefs suddenly feel provisional. They asked questions instead of offering futures.

This book is not interested in romance as resolution. It treats love as a mirror rather than a promise. A reflective surface that shows you not who the other person is, but who you become in their presence. What they activate. What they expose. What you mistake for destiny when it is, in fact, revelation.

Noir is not a person in the traditional sense. Noir is a catalyst. A placeholder for the kind of connection that arrives without invitation and leaves without explanation. The kind that intensifies quickly, not because it is meant to endure, but because it is meant to reveal.

There is a particular danger in these connections. Intensity can masquerade as alignment. Recognition can feel indistinguishable from belonging. The nervous system confuses activation with intimacy. Projection fills in the gaps that reality does not yet occupy.

Finding Noir does not romanticize this confusion. It sits inside it.

The book asks difficult, often uncomfortable questions:

What are we really responding to when someone feels familiar?

What parts of ourselves are we trying to reclaim through another?

At what point does longing become a refusal to see clearly?

Rather than offering answers, the book traces patterns—emotional, psychological, somatic. It examines how unhealed hunger can dress itself up as fate. How longing can borrow the language of spirituality. How the desire to be seen can override the willingness to see.

And yet, this is not a book that dismisses these connections as mistakes.

Some encounters are not meant to last because their purpose is not companionship, but consciousness. They arrive to interrupt, not to accompany. To destabilize the architecture of who you think you are, so something truer has a chance to emerge.

My mission in writing Finding Noir is not to instruct readers on what love should look like. It is to sit with them in the discomfort of asking what love is doing to them. To invite a more rigorous, compassionate form of inquiry—one that does not rush toward narrative closure.

This is a book for readers who are willing to look at their own projections without flinching. For those who suspect that the most powerful connections are not always the healthiest, but are often the most revealing. For those who are less interested in happy endings than in honest ones.

If this story leaves you unsettled, that may be the point.

Some books don’t want to be finished.

They don’t want to be consumed, resolved, or put away.

They want to be recognized.

Leave a comment