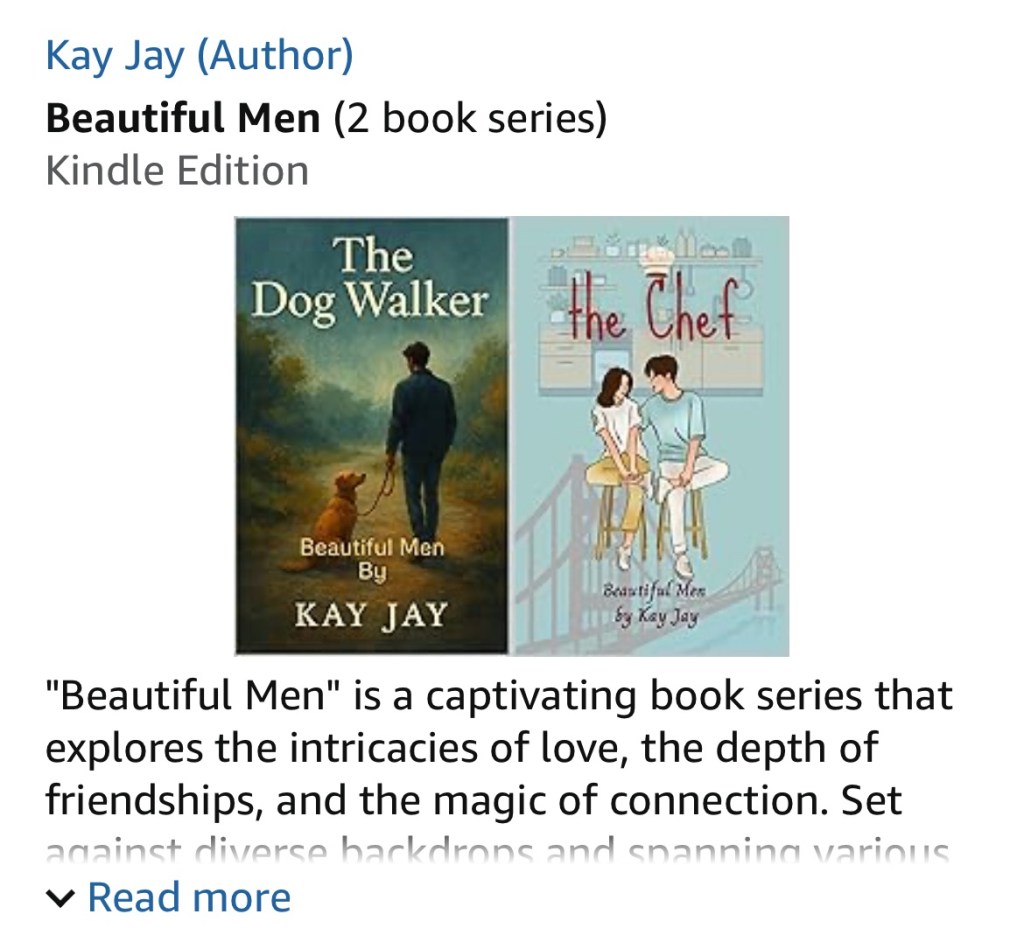

Beautiful Men: The Chef

What is your mission?

There was a time when nourishment felt transactional.

Food, care, attention—each arrived with an unspoken ledger. Nothing was allowed to remain unaccounted for. To receive was to incur obligation. To accept warmth without explanation felt irresponsible, even dangerous. Independence was not just a value; it was armor.

Beautiful Men: The Chef was written during the slow, often uncomfortable unlearning of that belief.

This book uses food as a language for intimacy—not desire, but care. Not pursuit, but presence. The kitchen becomes a site of quiet exchange, where nourishment is offered without spectacle and received without negotiation. In these moments, romance is stripped of its usual performances and redefined as attentiveness.

Here, romance is not about being chosen. It is about being tended to.

The figure of the chef is not heroic or idealized. He does not rescue or transform. He notices. He prepares. He offers sustenance without demanding recognition. And in doing so, he exposes a deeply ingrained discomfort: how difficult it can be to receive without immediately reaching for repayment.

This book asks an uncomfortable question: what if receiving is not weakness, but wisdom?

Self-sufficiency is often framed as moral virtue. We admire those who need little, who ask for nothing, who carry themselves without visible reliance. But Beautiful Men: The Chef interrogates this ideal, suggesting that it may be less about strength and more about fear—fear of dependency, of disappointment, of vulnerability disguised as autonomy.

Receiving requires a different kind of courage. It asks us to trust without control, to accept care without managing its consequences in advance. It demands a softness that cannot be optimized or defended.

My mission in this work is to challenge the mythology of self-sufficiency without romanticizing dependence. The book does not argue for passivity or entitlement. It argues for permission—for the ability to allow nourishment to arrive without guilt, justification, or self-correction.

Healing, as explored here, is not an achievement. It is not the result of discipline or effort. It is a shift in posture. A willingness to be affected.

Beautiful Men: The Chef is written for readers who have learned how to provide but forgotten how to receive. For those who equate independence with safety, and control with care.

If you’ve ever struggled to accept what is freely offered, this book is not asking you to change.

It is asking you to soften.