My first name, Kshitija, comes from Sanskrit. It means that which is born of the earth—the horizon where sky and land meet, a liminal line that exists not as a thing you can touch, but as a promise you keep walking toward. It is a word rooted in soil and sky at once, carrying the weight of belonging and the ache of longing. A name that suggests expansion without arrival, grounding without stagnation. From the beginning, it implies a life lived in between: between places, between selves, between what is and what could be.

That is where Kayra was born—from the same threshold. Though her name travels a different linguistic road, its spirit mirrors mine. Kayra, in many cultures, is associated with creation, continuity, and the unseen force that moves through nature rather than dominates it. Where Kshitija is the horizon, Kayra is the wind that moves toward it—not hurried, not fixed, but inevitable. Both names carry a quiet resilience, a femininity that does not perform itself loudly but endures, observes, holds.

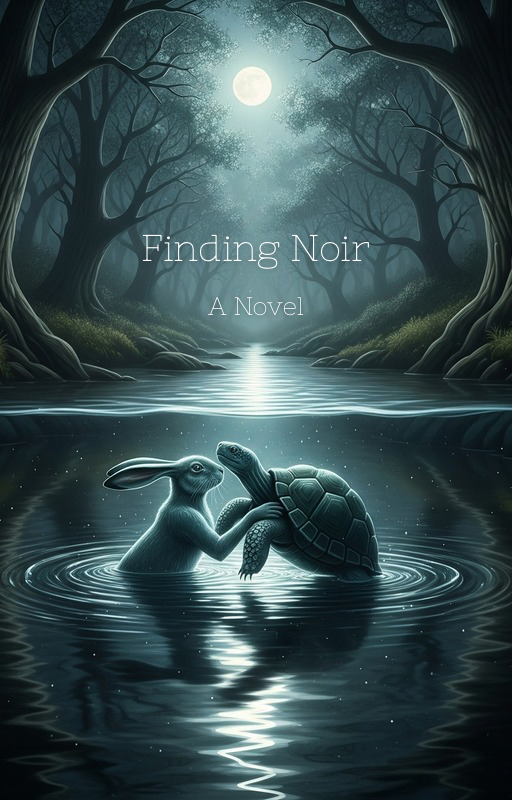

In Finding Noir, Kayra does not chase meaning; she recognizes it as something that unfolds through presence. Much like my name, her journey is not about conquest or arrival but about learning to stay—with uncertainty, with love, with absence. Kshitija taught me early that I would never be just one thing or belong to just one place. Kayra lives that truth on the page. She is not the destination of my story; she is its horizon.

In that way, writing Kayra felt less like invention and more like translation. Of taking the essence of my name—its earthiness, its quiet vastness, its eternal in-between—and letting it walk, speak, love, and lose. Both Kshitija and Kayra stand at the edge of something immense, not to cross it, but to witness it. And perhaps to invite the reader to stand there too.

And standing there—at that edge—does something subtle but irreversible. It strips away the urgency to define, to label, to arrive. The horizon teaches patience. It teaches that distance is not denial, and waiting is not weakness. Kshitija, as a name, carries this lesson quietly: you do not collapse into what you love, nor do you possess it. You remain present, rooted, and receptive.

Kayra inherits this wisdom not as philosophy, but as instinct. When Noir runs, when silence replaces certainty, she does not shrink to fill the void. She expands around it. This is the inheritance of the horizon—to hold vastness without panic. To understand that what leaves is not always lost, and what stays is not always visible. Kayra’s strength is not in pursuit, but in her capacity to remain open without self-erasure.

There is a particular loneliness in being named after a threshold. People expect decisiveness, arrival, resolution. But Kshitija—and Kayra—know better. They know that some lives are meant to be lived in motion, not forward, but inward. That love can be real even when it is unconsummated, unfinished, or unreturned in the ways stories usually demand.

In writing Finding Noir, I realized that Kayra was not my alter ego; she was my echo. She spoke the parts of me that learned to trust the unseen—to trust that meaning does not always announce itself with permanence. Sometimes it appears as a fleeting glance, a shared stillness, a resonance that survives separation.

If Kshitija is the place where earth meets sky, then Kayra is the act of standing there without asking the horizon to come closer. And Noir—perhaps—was never meant to be held, only encountered. A reminder that some connections exist not to anchor us, but to awaken us.