What do you complain about the most?

Diary Of Cliches

What I Complain About the Most

I complain about numbers.

Which is inconvenient, considering I’m a data scientist.

Not loudly. Not in dashboards or quarterly reviews. More in the private way one complains about the weather—aware it isn’t personal, yet feeling persistently misrepresented by it.

Numbers have never been hostile to me. They’ve simply been incomplete.

In 2016, my life required constant accounting. Energy was finite. Health came with caveats. Every decision demanded a calculation: cost versus capacity, intention versus aftermath. Chronic illness has a way of turning existence into a ledger, and you learn quickly how narrow the margins are.

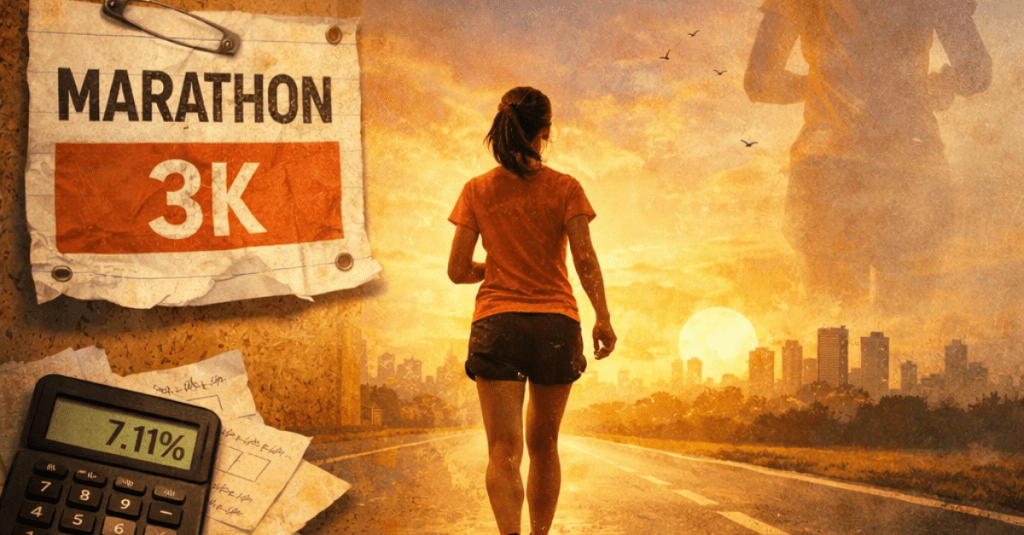

That was the year I began running.

Running was irrational by most metrics. The projections didn’t support it. The baseline was shaky. So I removed analysis from the process. I woke up before my mind had time to assemble hypotheses, put on my shoes, and ran while my thoughts were still offline.

The routine became automatic. Wake. Shoes. Run.

I ran on good days and on days that barely qualified as functional. Over time, the act stopped feeling exceptional and started feeling ordinary—which, I would later realize, is how meaningful change usually enters.

At some point, I wrote that I had run a marathon.

I hadn’t. It was three kilometers. Approximately 7.11% of one.

The number is correct. It’s also beside the point.

Here’s what the subconscious understood—what no model could capture: repetition creates identity. Consistency reshapes narrative. The mind does not require statistical significance to change; it requires evidence, accumulated quietly.

I wasn’t optimizing distance. I was retraining trust—with my body, with effort, with the idea of forward motion.

That three-kilometer run did something the data could not yet explain. It shifted the dominant variable in the system. I stopped being someone primarily managing limitation and became someone rehearsing possibility.

I became a runner—not because the distance justified the label, but because the behavior had already earned it.

This is why I complain about numbers.

They are indispensable. I build my professional life on them. They bring rigor, clarity, accountability. But they are poor witnesses to transformation. They report outcomes without observing the interior work—the courage, the repetition, the decision to continue without proof.

Words, on the other hand, are how we transmit meaning to the subconscious.

Calling it a marathon wasn’t an error. It was a translation. A narrative strong enough to carry change across the gap before the metrics caught up.

So yes, I complain about numbers.

Not because they are wrong—but because even the best ones arrive late to the truth.

Leave a comment